Mannhi's Race

My race began…

on the morning of my first solo trek to school as I waved goodbye to my dad from the driver’s seat. I was eighteen, too old to have my parents drive me around yet much too young to appreciate the comforts of such simplicities. Waiting in traffic, I looked around the car—in awe of my newfound freedom—and noticed the rings of coffee residue left by cups from my dad and I’s morning caffeine consumption. I’d never noticed these stains before since, as a kid, I would usually spend the entire car ride preoccupied with feeling sorry for myself for having to wake up so early for school.

“In the confinements of our tiny car that I would soon inherit, my dad and I experienced the world...”

Before I got my driver’s license, my dad drove me to school every morning. He’d wait in the driveway as I fumbled out of the house, holding one saddle oxford in each hand. In my younger years, I wore my shoes on my hands instead of my feet because the car ride meant one very important thing—a nice, long nap interrupted only by the dreaded yet inevitable arrival at school. I mean, who sleeps with shoes on? In 7th grade, my parents put me into an all-girls prep school forty-minutes away from home (hence the saddle oxfords, being a part of the required uniform and usually not any teenager’s ideal choice of footwear), which made my daily commute unusually long compared to those of other kids in my neighborhood.

“You are listening to Morning Edition on NPR News,” the radio would announce each morning as I settled in for the ride—and I’d usually know I was late if I heard Market Report instead of the time update. My dad lives and breathes for NPR. He says that it gives him a chance to access and see the world, paving a path for him to reach corners of the globe that he’ll never get a chance to visit. So each morning for as long as I can remember, Renee Montagne and Steve Inskeep would accompany us during our drives to school. Sprawled in the backseat, comforted by the lulling rhythm of the gliding car, I’d let the sounds and stories on the radio caress me to sleep.

When I started 8th grade, my dad began taking me to Starbucks. Slowly over the years, our once-a-week treats morphed into every-other-day stops until, inevitably, mornings with my dad were never complete until he had his red-eye in hand and I had whatever version of “coffee” I decided to have that morning. Our trips to school lengthened from forty to forty-five minutes because of my growing caffeine addiction. As my orders transitioned from Chocolaty Chip Frappuccinos to iced Americanos, I started wearing my shoes on my feet and slowly migrated to the front seat next to my dad. I don’t quite remember when I stopped sleeping in the car, but my journeys from home to school started to become some of the most endearing, life-changing memories of my life.

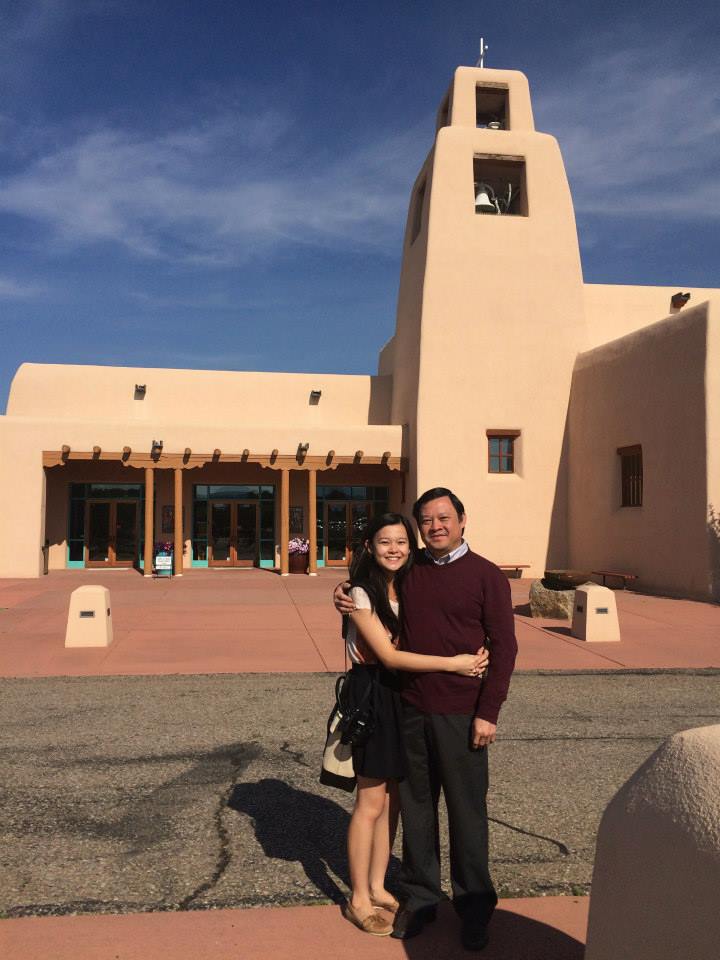

My dad is a humble man with a spectacular mind and an enormous heart. In the confinements of our tiny car that I would soon inherit, my dad and I experienced the world with our best friends, Renee and Steve. Conversing with the voices on the radio, we would discuss the economy, history, and global politics. In the front seat of a car that has never left Texas, my dad taught me the merits of the Japanese Bushido Code, the backstory behind the JFK assassination, the origin of the Taliban, the weakness of the Treaty of Versailles, and the rise of communism in Vietnam. And in the same car, he gave me advice on how to ask a guy out to Winter Formal, how to get over my first heartbreak, how to pick a college major, and how to make baked cheese in the microwave.

I used to get annoyed whenever my dad tried to help me solve everyday problems with politics or philosophy. His favorite solution to all my qualms? The trial of Socrates! The first time my dad mentioned Socrates, I was upset about a bad grade on an English paper: “You know, Socrates could have escaped his execution, but he decided to stay and receive his punishment. Socrates lived under Athenian law, so he had to uphold his legal responsibility to the law even though he was one of the government’s biggest opponents. He decided to hold onto his principles even if it meant losing his life.”

I responded to his seemingly random comment with confusion, “That’s cool and all, dad, but what relevance does that have to my grade?” And his point was that my teachers gave me a bad grade because they have certain standards that were meant to challenge and to teach me to be a better writer. I was only an 8th grader after all, and my teachers had a whole lifetime of experience. But then he also told me that, as an individual, I was my own person with my own style, and some people will like it while others won’t. Like Socrates, I also need to have my own principles. I’ll always remember what my dad said to me that day, “For the rest of your life, you’ll have to learn how to walk the line between abiding by the rules and breaking them.”

“...somewhere between my house and school and sometime between six and seven-thirty a.m. over the past decade, I grew up.”

The first day of my senior year I parked in my high school parking lot and found that I was on my own for the first time. I decided to sit in the car a little longer to finish the Story Corps segment. My dad wasn’t there to explain the things I didn’t understand but I realized that somewhere between my house and school and sometime between six and seven-thirty a.m. over the past decade, I grew up.

It suddenly dawned on me that one day my dad will no longer be there to tell me random stories about long-past philosophers, that there will be a lot of things in this world that I will never truly understand, that all the choices in my life are my own to make, and that I’d “have to learn how to walk the line between abiding by the rules and breaking them” all on my own.

My father has instilled in me a curiosity about the world and its people. He taught me to approach the world with humor and humility, to see everything as a learning opportunity, to go beyond structural limitations, and to find beauty in all things. Without realizing it, my dad wasn’t just using our caffeinated conversations to get me ready for the school day—he also managed to help prepare me for the never-ending race of life. Forty-minute drives to school with my dad eventually became solitary three-hour plane rides to Washington, D.C., for college—and now, I’m all on my own in New York City.

I’m not sure where I’m going at the moment (do any of us really?), but whenever I’m feeling especially lost or downhearted, I make myself a cup of coffee and turn on NPR to find the familiar voices that have guided me to where I am today. I think about my dad and about what he’d say to me—and I put my shoes on.